The case for more nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs) working in older people’s healthcare

Nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs) are essential to the provision of older people’s healthcare, working across acute, community and primary care as part of multidisciplinary teams. Despite this, there is a lack of data about how many nurses and AHPs currently work with older people and how many are needed in order to provide care for the ageing population. This report is our first attempt to fill that gap.

This report sets out, with caveats, the data that currently exists regarding nurses and AHPs working in older people’s healthcare in England and suggests how this workforce could be better utilised to ensure that older people have access to the care they need, where and when they need it. We hope that those making decisions around the future workforce needs for the NHS and social care heed these recommendations.

Background

In May 2023, BGS published The case for more geriatricians which proposes there should be a ratio of one geriatrician for every 500 people aged over 85 in the UK.

This figure was based on analysis of geriatrician numbers across the country, noting that parts of the country where this ratio was achieved were delivering services such as peri-operative care, oncogeriatrics and Hospital at Home, whereas areas that did not meet this ratio struggled to provide even basic geriatric medicine services. In order for this ratio to be achieved however, 1,846 more geriatricians would need to be trained by 2030. Given it takes, on average, 16 years to train a consultant geriatrician, this is clearly unachievable. Nevertheless, setting a benchmark like this gives a clear signal of the current shortfall in geriatric medicine consultants, and the need to do systematic long-term workforce planning and resourcing to be prepared for a population that is ageing.

We have always been clear that training and recruiting additional geriatricians is only one part of the picture. Older people’s healthcare is a multiprofessional endeavour with healthcare professionals from nursing, pharmacy and the allied health professions playing key roles in provision of care across the country. Individuals from these professions comprise around a quarter of the BGS membership. It has always been our intention to publish data on wider older people’s healthcare workforce but we have struggled to find comparable data for the other professions. We focused on doctors in the first instance because we had easily accessible data for doctors from the Royal College of Physicians census.

While this report attempts to fill that gap, it is not perfect and we have set out many caveats and concerns. However, we feel it is important to draw a line in the sand, as it were. This report sets out the data we have and how we got it and draws some conclusions based on that data. This is not the end of the conversation.

Methodology

This report is based on data provided by NHS England in response to a request under the Freedom of Information Act.

While there was initially some confusion about whether this data existed, we became aware that it was held by Health Education England, which was at the time being merged with NHS England. This data is held in the Workforce Intelligence Portal which is accessible to anyone with an NHS email address, on the condition that they did not share the data. This meant that BGS staff were not able to access the data and any BGS member who did gain access would be unable to share it. We contacted the data team at NHS England to ask for access to the database. We believed that by accessing the database and conducting this analysis, we could help NHS England to better understand the workforce caring for the NHS’s largest user group – older people. This request was denied.

We then requested the data, rather than access to the database, through the Freedom of Information Act, describing exactly where the data was held and how it can be accessed. This request was worded as follows:

Under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 I am writing to request the following information:

Numbers of nurses and allied health professionals working in older people’s services across England, by grade and geographic location.

This data is held in the Workforce Intelligence Portal and can be accessed through the following steps:

Dashboards and reporting > Current > ESR Workforce > ESR (area of work overview secondary care) > Elderly care medicine. †

This request was granted and the data provided to us.

† BGS does not condone use of the word ‘elderly’ and would not usually use it in our publications.

However, this is the categorisation used in the database and therefore we have used it to be consistent.

Caveats

The data is not perfect and we have doubts about how accurate it is. In this section we will outline some of our concerns about the data.

It is not clear to us whether this data includes all nurses and allied health professionals working in older people’s healthcare across all settings. While the data is held in a part of the database regarding secondary care, it is unclear whether nurses and allied health professionals who are employed by acute trusts but work in the community are included. It seems likely that nurses and allied health professionals working in primary care or directly employed by community trusts are not included in these numbers. Any nurses or AHPs working in social care or in private practice will not be included in these numbers, even if they are providing services to NHS patients. As such, the numbers presented here are likely to be a considerable under-estimate.

It is also not clear how nurses and allied health professionals are categorised as working in ‘elderly care medicine’, ie, whether this is self-reported or not. It is likely that a large number of nurses and allied health professionals who primarily work with older people but do not identify as experts in older people’s healthcare (such as those working in district nursing) are not included in these numbers.

The data provided is a snapshot of the nursing and AHP workforce in England on a specific day in May 2023. The workforce is clearly fluid and therefore the numbers will not always be accurate. Even with this in mind, some of the numbers seem particularly low, especially those around AHPs.

We also cannot tell from the data which professions the AHPs are from. We know that all of the 14 allied health professions are involved in older people’s healthcare to some extent but it is likely that more physiotherapists and occupational therapists will identify as specialising in this area. It is also likely that many AHPs will work in more general services and will not be identified as working specifically in older people’s healthcare. As such, it is very likely that this data undercounts AHPs working with older people.

We know that this data does not include the entire workforce caring for older people. Pharmacists, for example, are a valuable part of many multidisciplinary teams but are not included within this data as they are not classified as one of the allied health professions.

As health is a devolved issue, the data only includes nurses and allied health professionals working with older people in England. While it is likely that the general themes of this report are relevant across the four nations, we know that each of the nations faces specific challenges related to workforce. We are considering how we can gain access the equivalent data for each of the nations.

The data

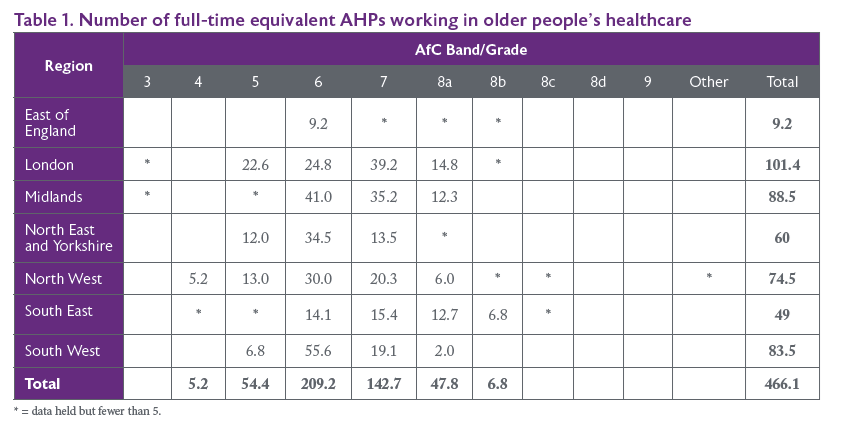

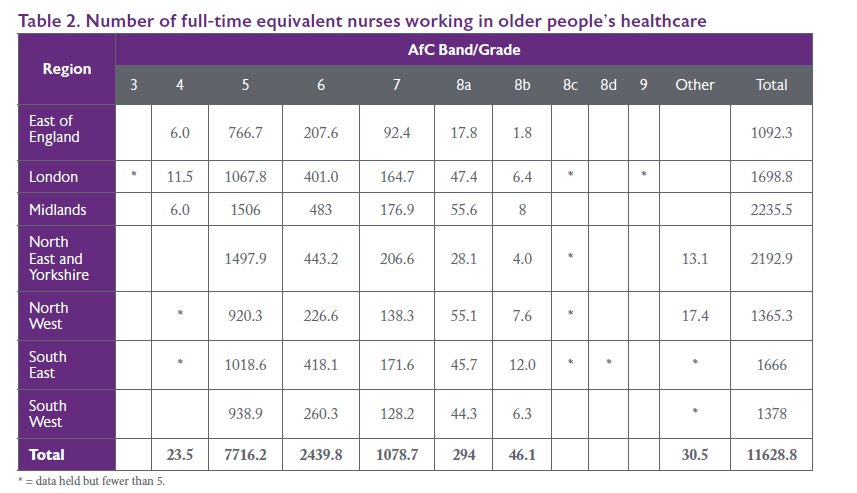

For the purposes of transparency, we are providing the exact data, as provided to us. The data is set out in tables 1 and 2.

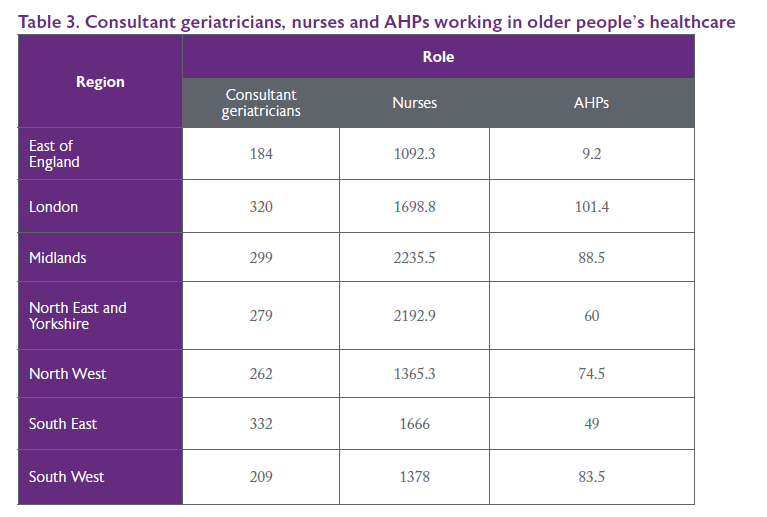

In table 3 we compare numbers of nurses and AHPs working in older people’s healthcare to consultant geriatricians. The numbers used for consultant geriatricians were obtained from the RCP census of consultant physicians.

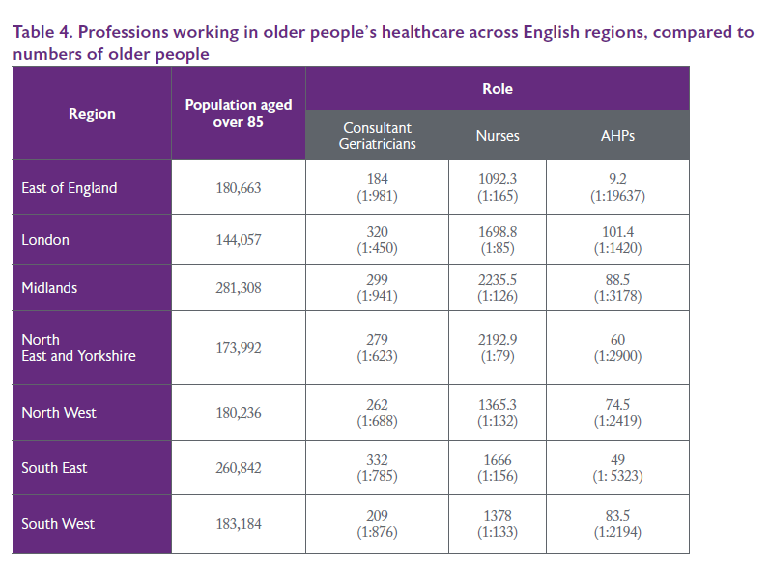

In table 4, we compare each group to the numbers of people aged 85 and over in each region. When we published our Case for more geriatricians, we used this comparison to suggest a ratio of how many consultant geriatricians would be needed to adequately care for the ageing population. The ratio we suggested was one geriatrician per 500 people aged 85 and over. This was based on areas such as London where this ratio is being met and services are better able to provide additional services such as POPS and oncogeriatrics. We had hoped to suggest a similar ratio for nurses and AHPs.

Low numbers of AHPs across the country make this task impossible for that group. However, areas that are close to the 1:500 ratio for geriatricians also appear to roughly meet a ratio of one older person’s nurse for every 80 people aged over 85. However, the Agenda for Change banding system for nurses makes it difficult to say exactly what the ratio should be as ‘nurses’ are not a homogenous group. Nurses from across the bands have different skills, experiences and abilities and a multidisciplinary team should have individuals with a range of skills and experiences.

Discussion

Unsurprisingly, the largest number of nurses working with older people are at band 5 level, which is the entry-level band for newly registered nurses. 66% of nurses working with older people are in this band. However, this does not mean that all of the nurses working at this level are newly qualified – many may be highly experienced but have chosen, for personal or professional reasons, not to pursue promotion. This group is likely to include staff nurses working in older people’s services across the country who are crucial to providing high quality care to older people.

There are more AHPs working at band 6 level than any other grade. It is difficult to say why this is, although it may be because newly registered AHPs are more likely to work in services that provide care to a range of population groups and therefore are less likely to be identified as specialists in older people’s care. AHPs working at band 6 and above may be more likely to be working in specialist older people’s services.

It is difficult to tell from the data available how many of these people are working in patient-facing roles. Generally speaking, nurses and allied health professionals who are working at band 8 and above are more likely to have taken on leadership roles which are less likely to be patient-facing. However, some of those working at senior levels will be advanced clinical practitioners or consultant practitioners and will remain patient-facing. While these roles are becoming more common, it is likely that at least some of the senior-banded clinicians included in this data are in leadership roles that are not patient-facing. Only 3.3% of nurses and AHPs in total are working at band 8 or above, suggesting that there is considerable potential for expansion of clinical roles at these levels.

As mentioned previously, the Agenda for Change banding system for nurses and AHPs makes it difficult to recommend a ratio for nurses or AHPs compared to the population of older people. For instance, while regions might have similar numbers of clinicians working at band 5, there is significant geographic variation in the numbers of clinicians working at more senior bands. While all members of the multidisciplinary team contribute different skills to the care provided to patients and specialist doctors have a specific leadership role, nurses and AHPs at higher bands can take on leadership roles, prescribe and make decisions about patient care. Areas that find it difficult to recruit into consultant geriatrician posts may find that employing more nurses and AHPs at more senior levels helps to ensure that senior level clinicians are available and that a consultant geriatrician’s limited time is spent doing the tasks that need to be done by a doctor.

Conclusion

Older people use the NHS more than any other population group and as the population continues to age, this trend will continue. It is essential that the workforce is adequately resourced and skilled to provide high quality care for older people across primary, community and acute services. It is difficult to plan services for an ageing population without a clear baseline of the current workforce.

However, it seems certain that more nurses and AHPs with expertise in older people’s healthcare are needed to work across all bands and all healthcare settings. A multidisciplinary workforce at a variety of skill levels will be crucial to addressing and ensuring that older people, both now and in the future, can access the care they need, where and when they need it. Planning for this workforce must be informed by accurate, timely data.

Key points

Data

a. Accurate, complete data about the number of nurses and AHPs working with older people from all regions should be collected.

b. Systems should be required to produce this data annually and publish it publicly.

c. Data should include more detail about the roles held by nurses and AHPs working with older people to ensure that the people carrying out these crucial roles are properly counted.

d. Data on these professions should be available across acute, community, primary and social care.

Career development and training

e. The Department of Health and Social Care should promote career paths allowing nurses and AHPs to progress in their careers while remaining clinical. Advanced practitioner and consultant practitioner roles have existed for many years but are still relatively under-utilised.

f. All healthcare professionals (with the exceptions of those working in obstetrics or paediatrics) should have the skills needed to care for people living with frailty, cognitive impairment and other conditions associated with ageing.